I was invited to guest lecture at an Executive MBA program session at Louisiana State University by a family friend who teaches law at the University. He thought it would be interesting to explore the Affordable Care Act in the context of industry leadership. Below is my talk, in a nutshell:

A medtech marketing professional explores the principles behind and examples of industrial innovations that have the potential to reduce cost, increase access, and increase quality in the U.S. healthcare system.

Monday, November 7, 2011

Wednesday, October 19, 2011

Another failure of Government Healthcare Reform: CLASS for Long Term Care

We all know the U.S. population is aging, and that Long Term Care is going to be a huge issue. It is so expensive that people are now buying LTC insurance, but rates even when one is healthy are exorbitant. The Affordable Care Act introduced the CLASS Act to offer a LTC benefit of $50/day for help with activities of daily living. After 19 months of work, they determined that a solution could not be found.

Takeaway: the actual CARE in LTC has to be AFFORDABLE, through either consumer-driven and consumer-priced solutions or LTC insurance that works with HC insurance in an AFFORDABLE way. Lots of room for innovation here!

October 18, 2011, 7:00 am

Jim Lo Scalzo/European Pressphoto AgencyKathleen Sebelius, health and human services secretary, at a House committee hearing in July.Let the post-mortem on the Class Act begin.

Jim Lo Scalzo/European Pressphoto AgencyKathleen Sebelius, health and human services secretary, at a House committee hearing in July.Let the post-mortem on the Class Act begin.

The health and human services secretary, Kathleen Sebelius, charged with carrying out this first-ever national program of voluntary long-term care insurance, made official on Friday what had been speculated for several weeks: the administration was shutting down Class. After 19 months of research and consultation, “we have not identified a way to make Class work at this time,” she said.

But was it really unsound? Was it impossible to offer to those who needed help with the activities of daily living a $50-a-day benefit ($18,000 a year) that would help ease the huge financial burden of long-term care? The insurance industry veteran hired to serve as the program’s chief actuary, Robert Yee, begs to differ — or at least, he begs to defer judgment.

Mr. Yee, whose dismissal last month first signaled that the program was in trouble, told me on Monday that when it came to setting benefits and premiums, planning for Class remained at a fairly early stage. It would have taken another six months, he said, to come up with the numbers. But “from an actuarial perspective, we can make it work,” he said.

The primary stumbling block, as Class critics have pointed out since it was enacted as part of the Affordable Care Act, was the potential for so-called adverse selection — the chance that too many people needing benefits (because they were already sick or disabled or soon would be) would enroll without enough younger, healthier people joining up, paying premiums and balancing the risk.

“Clearly, everyone agreed that if you don’t control that, you don’t have a program,” Mr. Yee said.

On Friday, Ms. Sebelius submitted a 48-page report on her department’s attempts to come up with a marketable, sustainable program. In the appendix, of which Mr. Yee was an author, you can see the actuaries grappling with adverse selection and trying out various ways to limit the damage.

Private insurers rely on underwriting. You can’t get long-term care insurance if you’re already sick, and the rates get awfully high if you’re already old.

The Class program could not have resorted to such remedies, but Mr. Yee proposed other modifications, like “phased enrollment,” in which large employers offer the plan first before individuals can sign up. Or benefits and premiums that increased over time on a fixed schedule, so younger workers could pay less initially, then more as their income increased. Or “temporary exclusion”: no benefits for 15 years if the need for help arises from a serious medical condition that already existed when someone enrolled. Or some combination thereof.

“These are tools and techniques private insurers use in both health and life insurance,” Mr. Yee said. He wanted the Health and Human Services Department to use them and to keep working on the problem.

The greater obstacle might have been not actuarial but legal. As the legal analysis in the report points out, the Class Act statute imposed certain requirements that were at odds with some solutions the actuaries contemplated. The department’s report is full of phrases like, “We conclude that there is no statutory basis for this kind of approach.”

Mr. Yee — who said he didn’t hear of these qualms until the report’s publication — doesn’t see why they should bring the whole program to a halt. “Tell the Congress to make very simple changes in the language,” he suggested. Some legislative fixes might amount to only a sentence. “If people believe a long-term care insurance program is a good thing, it’s easy,” he said.

Telling Congress to do anything isn’t easy these days but, said Mr. Yee, “I’m a little disappointed” that the administration won’t give it a try. “It seems like they gave up. In my world, quitting is not an option.” His bosses evidently saw things differently.

One issue he and Ms. Sebelius agree on, however, is that the need for long-term care will only grow. Most developed nations have mandatory long-term care insurance, Mr. Yee pointed out. “You have to take baby steps. I’m having problems with people saying they care about this issue but not doing enough.”

Ms. Sebelius announced on Friday that “even as we suspend work on implementing Class, we are recommitting ourselves to the ultimate goal of making sure Americans can get the long-term care they need.”

Good to know. We’ll be waiting to hear what she has in mind.

Takeaway: the actual CARE in LTC has to be AFFORDABLE, through either consumer-driven and consumer-priced solutions or LTC insurance that works with HC insurance in an AFFORDABLE way. Lots of room for innovation here!

October 18, 2011, 7:00 am

Behind the Class Act, a Numbers Game

By PAULA SPANThe health and human services secretary, Kathleen Sebelius, charged with carrying out this first-ever national program of voluntary long-term care insurance, made official on Friday what had been speculated for several weeks: the administration was shutting down Class. After 19 months of research and consultation, “we have not identified a way to make Class work at this time,” she said.

But was it really unsound? Was it impossible to offer to those who needed help with the activities of daily living a $50-a-day benefit ($18,000 a year) that would help ease the huge financial burden of long-term care? The insurance industry veteran hired to serve as the program’s chief actuary, Robert Yee, begs to differ — or at least, he begs to defer judgment.

Mr. Yee, whose dismissal last month first signaled that the program was in trouble, told me on Monday that when it came to setting benefits and premiums, planning for Class remained at a fairly early stage. It would have taken another six months, he said, to come up with the numbers. But “from an actuarial perspective, we can make it work,” he said.

The primary stumbling block, as Class critics have pointed out since it was enacted as part of the Affordable Care Act, was the potential for so-called adverse selection — the chance that too many people needing benefits (because they were already sick or disabled or soon would be) would enroll without enough younger, healthier people joining up, paying premiums and balancing the risk.

“Clearly, everyone agreed that if you don’t control that, you don’t have a program,” Mr. Yee said.

On Friday, Ms. Sebelius submitted a 48-page report on her department’s attempts to come up with a marketable, sustainable program. In the appendix, of which Mr. Yee was an author, you can see the actuaries grappling with adverse selection and trying out various ways to limit the damage.

Private insurers rely on underwriting. You can’t get long-term care insurance if you’re already sick, and the rates get awfully high if you’re already old.

The Class program could not have resorted to such remedies, but Mr. Yee proposed other modifications, like “phased enrollment,” in which large employers offer the plan first before individuals can sign up. Or benefits and premiums that increased over time on a fixed schedule, so younger workers could pay less initially, then more as their income increased. Or “temporary exclusion”: no benefits for 15 years if the need for help arises from a serious medical condition that already existed when someone enrolled. Or some combination thereof.

“These are tools and techniques private insurers use in both health and life insurance,” Mr. Yee said. He wanted the Health and Human Services Department to use them and to keep working on the problem.

The greater obstacle might have been not actuarial but legal. As the legal analysis in the report points out, the Class Act statute imposed certain requirements that were at odds with some solutions the actuaries contemplated. The department’s report is full of phrases like, “We conclude that there is no statutory basis for this kind of approach.”

Mr. Yee — who said he didn’t hear of these qualms until the report’s publication — doesn’t see why they should bring the whole program to a halt. “Tell the Congress to make very simple changes in the language,” he suggested. Some legislative fixes might amount to only a sentence. “If people believe a long-term care insurance program is a good thing, it’s easy,” he said.

Telling Congress to do anything isn’t easy these days but, said Mr. Yee, “I’m a little disappointed” that the administration won’t give it a try. “It seems like they gave up. In my world, quitting is not an option.” His bosses evidently saw things differently.

One issue he and Ms. Sebelius agree on, however, is that the need for long-term care will only grow. Most developed nations have mandatory long-term care insurance, Mr. Yee pointed out. “You have to take baby steps. I’m having problems with people saying they care about this issue but not doing enough.”

Ms. Sebelius announced on Friday that “even as we suspend work on implementing Class, we are recommitting ourselves to the ultimate goal of making sure Americans can get the long-term care they need.”

Good to know. We’ll be waiting to hear what she has in mind.

Paula Span is the author of “When the Time Comes: Families With Aging Parents Share Their Struggles and Solutions.”

2010 Good Year, but Medtech Needs New Ways to Sustain Innovation, Says E&Y

| http://medicaldevicesummit.com/Main/News/2010-Good-Year-but-Medtech-Needs-New-Ways-to-Susta-504.aspx Wednesday, September 28, 2011 9:21 AM |

| 2010 Good Year, but Medtech Needs New Ways to Sustain Innovation, says E&Y Report While 2010 was a better year in terms of revenues and more deal-making, venture capital funding fell 13 percent; the industry will need to revamp sales and marketing, and innovation efforts to show outcomes, offer solutions rather than products and cater to ‘super consumers,’ the Medical Technology Report 2011 concludes. |

For publicly-traded medtech companies in the US and Europe, 2010 was a better year than 2009 in terms of growth rates, persistent funding challenges for many companies, along with regulatory and pricing pressures and fundamental changes in global health care has pushed companies to find new ways to sustain innovation in the future. This is the conclusion of Ernst & Young’s Pulse of the Industry: Medical Technology Report 2011 released this week at AdvaMed 2011.

“The medtech industry delivered an impressive performance in 2010 in the face of continued strong economic headwinds, but a closer look beyond the numbers shows that deep challenges remain for most industry members,” said John Babitt, Ernst & Young's Medtech Leader for the Americas.

"From increased payer pressure to demonstrate value, heightened regulatory scrutiny, a continued tight funding climate and a rapidly changing customer base, the industry's ability to innovate is under increasing strain. To respond effectively, companies will need to expand beyond the products they have historically offered to solutions built for an increasingly outcomes-focused system."

The report included various findings such as:

- Net income for non-conglomerates in the US and Europe increased 43 percent from 2009 to $17.4 billion; total revenues for all public medtech companies was $315.9 billion (a 4 percent growth from the previous year).

- Venture capital investment fell 13 percent in 2010 compared to the prior year; while the fall was 15 percent in the US (to $3.5 billion), in Europe venture investment grew 4.7% to $707 million.

- IPO activity picked up in 2010, after two years of sluggishness; nine medtech companies in US or Europe completed IPOs in 2010 compared to two in 2009, grossing a total of US$568 million.

- Total value of mergers and acquisitions in the US and Europe rebounded to $30.6 billion in 2010, up from a historically low $15.7 billion in 2009. Average deals size increased from $175 million to $245 million.

The report also highlighted challenges that the industry was facing such as the pressure to demonstrate health outcomes: “A company's success or failure in the medtech industry of the future will not be based simply on how many products they sell but on their ability to demonstrate how they are improving health outcomes.”

The emergence of highly informed and empowered “super-consumers" will also force companies to adapt and target their offerings rather than simply focusing on physicians.

The report concluded that these changes in the medtech ecosystem will require medtech companies to fundamentally reinvent core parts of their business model, including what they sell, how they sell it, and how they develop these new offerings, throwing up challenges like:

- Expand from products to solutions and seek new ways to extract value from the information they have.

- Revamp the sales and marketing end of their business model.

- Better capitalize on opportunities to mine new product ideas from more widely distributed information networks that will be part of the health care ecosystem of tomorrow.

“Medtech companies have always taken on substantial risk to innovate new products and technologies," said Glen Giovannetti, Ernst & Young's Global Life Sciences Leader. "However, risk now stems not only from product development, but also from a host of other pressures. To respond, companies will need to innovate new business models. If risk has moved beyond the product, so too must innovation."

The End of Medicine as We Know It - Oct. 17th UST Physician Leadership Symposia

I was fortunate to attend the 12th Annual Physician Leadership Symposium University of St. Thomas on October 17, sponsored by leading Minnesota physician William E. Petersen's endowment and presented by Allina Hospitals and Clinics, Abbott Northwestern Hospital Foundation, and the health care programs of the University of St. Thomas. The event featured consultant James Orlikoff, named one of the 100 most powerful people in healthcare by Modern Healthcare magazine and National Advisor on Governance and Leadership to the American Hospital and Health Forum, Senior Consultant to the Cnter for Health Care Governance, speaking about Leadership in a Time of Reform.

Given this daunting topic, Mr. Orlikoff did an outstanding job of distilling down the issues to the critical few, and ended with the conclusion that Medicine as Physicians now know it is over. Why? Let's take a look at a few of the points Mr. Orlikoff made about the ‘big picture’ drivers of healthcare reform:

• Why has healthcare reform passed now, after so many previous attempts? At this time, the U.S. National Debt has reached the point where we are in crisis. To get out of that crisis, we have to address Medicare as one of the largest cost drivers in the government's budget (along with Social Security and Defense.) As we remember, the U.S. economy was in limbo while the government voted on raising the debt ceiling in August 2011 to $14.3 trillion, from the $12.4 trillion level set in December 2009, the 6th time Congress raised the debt limit since 1917's Second Liberty Bond Act. The National Debt is now close to the entire annual Gross Domestic Product of the U.S., which was $15 trillion in 2011. Work is now happening in a subcommittee to find $1.3 trillion of savings by November 2011, with a Congressional vote in December; if if can't be found and agreed upon, the U.S. economy could again be thrown into a tailspin where we either 1) default on our debts, or 2) raise the debt ceiling again, both of which would have dramatic implications for the U.S. debt rating and could throw our economy into the worst depression since the Great Depression in 1929-1941. With the huge economic importance of resolving this situation, the political environment was ready to attach healthcare reform, where before the urgency didn't allow politicians to step on the dangerous turf of removing social benefit programs.

* Since introduction of Medicare by Lyndon Johnson with the Social Security Act in 1965, when the "average" life expectancy (influenced by WWII and the pandemic flu) was 65 so benefits were set at 65, the program now covers over 48 million people. Medicare was modeled after Otto von Bismarck who implemented an "illusory safety net" in Germany after WWI that provided medical covereage for people >65; at that time, 65 was life expectancy. Now it is more like 92, Also, using the AVERAGE life expectancy vs. the end value of life expectancy greatly increases the number of potential enrollees at any age, and the choice of 65 has created a great Medicare pool. (great timeline at http://www.kff.org/medicare/medicaretimeline.cfm).

* Economically, healthcare expenditures in the U.S.were ~ 17% of GDP in 2009 , compared to 6-12% of much of the rest of the world, and are projected to be ~20% of GDP by 2020. In 2020, Medicare/Medicaid will comprise ~ 1/2 of healthcare spending, making the government effectively a single payor system for the U.S., and spending it's share, or 10% of U.S. GDP, on it. Healthcare is not "value-added" to society; though there may be measurable economic gains from healthcare spending in the workforce through increased productivity, by definition, Medicare is for people > 65 when people are no longer working, and much of our healthcare spending is at end of life as well.

* For company-sponsored health plans, each employee costs ~ $20k/year to insure. This key fact makes the U.S. extremely uncompetitive in the global marketplace for goods and services, as has been alluded to in the auto industry: for the same steel and labor costs, it still costs the U.S. xx% more to produce a car because it has to factor in healthcare costs, so that it can't set a price competitive to say, Japan, which spent ~8.5% of GDP on healthcare in 2009 and still be as profitable. When a consumer see a blouse made in the U.S. for sale for $85, and then another similar one of the same quality on the next rack selling for $15 made in China, consumers make an economic value decision for themselves; pricing in the "morality" of supporting the U.S. healthcare system expense is a losing battle in the global marketplace. (in 2001 China's spending was 5.5% GDP; now their GDP is much higher http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_health_in_the_People%27s_Republic_of_China). The same goes for ALL goods and services made in the U.S.; consumers aren't willing to pay for "employees healthcare." Therefore for the U.S. to be economically competitive with the world, we need to reduce the cost of healthcare that is absorbed in our product costs.

* In addition to being tremendously expensive, the historical "cost-plus" environment of healthcare reimbursement has led to a grossly inefficient system with 30-50% waste due to fraud, re-work, and ill-applied medical procedures that don't result in quality outcomes, increased QoL and length of life. It is also worth noting that even if Medicare were not financially broken by inefficiency and other waste, the demographics of the baby boomer generation will break the system when more baby boomers on on Medicare than employed people putting into the system. As previously noted, much healthcare spending in the U.S. occurs at end of life, with spending in the $20-$30k level per person. If Medicare were able to reduce the waste by 50% in the system, even for just Medicare, at current projections the U.S. would save 5% of our GDP! Thus the government reform effort is focusing on implementing Electronic Health Records to drive efficiency and starting to pay for Quality (Performance) / Cost in healthcare, true value meaures, vs. "Volume" of procedures (fee for service.) The metrics of success will evolve to greater efficiency - PCP's in the U.S. see ~ 40 patients / day; in England and Singapore, they see ~ 60. Processes and procedures will need to enable physicians to perform at this level.

* To reduce Medicare spending, the gov't has introduced the concept of reducing physician payment rates, but so far lobbying has prevented the measures from being implemented. Even so, the rates haven't kept pace with expenses, so that while historically "any monkey could make $ with Medicare," now physicians and hospitals need higher-paying private insurance reimbursement as part of their insured mix to break even. And as previously noted, the % of private insured is declining as demographics shift, and employers have reached a threshold on the amount of healthcare $ they can contribute to insurance plans, so private insurance rates need to come down as well.

* One big piece of the Affordable Care Act is the Individual Mandate, which requires all citizens to obtain healthcare coverage. The concept actually originated with Bob Dole and Newt Gingrich in the 1990's as a "individual responsibility" item. This will be made possible by employer requirements and the development of state-sponsored insurance exchanges. (Many companies have already indicated that with healthcare reform, they will elect to pay the $2k govt. fine and allow employees to find insurance through the state-sponsored health exchanges.) The concept of increasing the insured base may be good, because it assumes that if people are insured they will prevent more costly healthcare, as well as contribute more productively to our economy, but the legislation has been challenged for being unconstitutional. (I WILL ADDRESS THIS TOPIC IN MORE DETAIL IN A FUTURE BLOG ENTITLED "SINCE WHEN DID HEALTHCARE BECOME AN UNALIENABLE HUMAN RIGHT?)

* So how will this all work out? I wish I had taken better notes re: a McKinsey study that laid out three options: 1) , 2) , 3) belt tightening.

Personally I believe that Option 3, "belt tightening" is exactly where are are going, first with 1) limited rationing and then to 2) more progressive measures such as "process improvements" which I introduced in a previous blog post, 3) continued innovative insurance optionsto make it affordable and accessible, and 4) dramatic implementation of Health Care Directives on the social side. True process improvement requires first of all a thorough understanding of what the process is (and I think we're believing that medicine is, after all, conducive to process and not just dr's art) and then defining how that process can be streamlined and costs taken out. This will take tremendous time & effort to maintain the quality standards that U.S. citizens expect from our healthcare system while reducing costs, but relatively simple areas may be spun out. Regina Herzliner's "focused factory" concept fits the bill here. The evolvement of Minute-Clinic and Virtuwell/Zipnosis type healthcare delivery for more simple care situations provide examples, as well as specialized surgery centers for hernia repair, cardiac, etc. FUTURE BLOG POSTS TO ADDRESS: Richard Bohmer's Care Pathways and Regina Herzlinger's Market & Consumer Driven Healthcare. "If McDonalds can make perfect french fries all the time, why can't our healthcare system deliver quality outcomes at a reasonable price?"

* Mr. Orlikoff concluded the Symposia with two thoughts from historical thinkers:

1) Darwin's dying words were "they got it wrong - it isn't survival of the strongest (fittest,) it's survival of the most adaptable", and

2) Looking to Adam Smith's Division of Labor economics, do we believe that the U.S. is going to allow physicians / healthcare to bring down the U.S. economy, or with the U.S. economy bring down physicians / healthcare?

We can guess where people will side on that battlefront. I look forward to continuing to "crack the nut" of how industry can be the lead player in reforming our healthcare system to reduce cost, increase access, and increase quality.

Given this daunting topic, Mr. Orlikoff did an outstanding job of distilling down the issues to the critical few, and ended with the conclusion that Medicine as Physicians now know it is over. Why? Let's take a look at a few of the points Mr. Orlikoff made about the ‘big picture’ drivers of healthcare reform:

• Why has healthcare reform passed now, after so many previous attempts? At this time, the U.S. National Debt has reached the point where we are in crisis. To get out of that crisis, we have to address Medicare as one of the largest cost drivers in the government's budget (along with Social Security and Defense.) As we remember, the U.S. economy was in limbo while the government voted on raising the debt ceiling in August 2011 to $14.3 trillion, from the $12.4 trillion level set in December 2009, the 6th time Congress raised the debt limit since 1917's Second Liberty Bond Act. The National Debt is now close to the entire annual Gross Domestic Product of the U.S., which was $15 trillion in 2011. Work is now happening in a subcommittee to find $1.3 trillion of savings by November 2011, with a Congressional vote in December; if if can't be found and agreed upon, the U.S. economy could again be thrown into a tailspin where we either 1) default on our debts, or 2) raise the debt ceiling again, both of which would have dramatic implications for the U.S. debt rating and could throw our economy into the worst depression since the Great Depression in 1929-1941. With the huge economic importance of resolving this situation, the political environment was ready to attach healthcare reform, where before the urgency didn't allow politicians to step on the dangerous turf of removing social benefit programs.

* Since introduction of Medicare by Lyndon Johnson with the Social Security Act in 1965, when the "average" life expectancy (influenced by WWII and the pandemic flu) was 65 so benefits were set at 65, the program now covers over 48 million people. Medicare was modeled after Otto von Bismarck who implemented an "illusory safety net" in Germany after WWI that provided medical covereage for people >65; at that time, 65 was life expectancy. Now it is more like 92, Also, using the AVERAGE life expectancy vs. the end value of life expectancy greatly increases the number of potential enrollees at any age, and the choice of 65 has created a great Medicare pool. (great timeline at http://www.kff.org/medicare/medicaretimeline.cfm).

* Economically, healthcare expenditures in the U.S.were ~ 17% of GDP in 2009 , compared to 6-12% of much of the rest of the world, and are projected to be ~20% of GDP by 2020. In 2020, Medicare/Medicaid will comprise ~ 1/2 of healthcare spending, making the government effectively a single payor system for the U.S., and spending it's share, or 10% of U.S. GDP, on it. Healthcare is not "value-added" to society; though there may be measurable economic gains from healthcare spending in the workforce through increased productivity, by definition, Medicare is for people > 65 when people are no longer working, and much of our healthcare spending is at end of life as well.

* For company-sponsored health plans, each employee costs ~ $20k/year to insure. This key fact makes the U.S. extremely uncompetitive in the global marketplace for goods and services, as has been alluded to in the auto industry: for the same steel and labor costs, it still costs the U.S. xx% more to produce a car because it has to factor in healthcare costs, so that it can't set a price competitive to say, Japan, which spent ~8.5% of GDP on healthcare in 2009 and still be as profitable. When a consumer see a blouse made in the U.S. for sale for $85, and then another similar one of the same quality on the next rack selling for $15 made in China, consumers make an economic value decision for themselves; pricing in the "morality" of supporting the U.S. healthcare system expense is a losing battle in the global marketplace. (in 2001 China's spending was 5.5% GDP; now their GDP is much higher http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_health_in_the_People%27s_Republic_of_China). The same goes for ALL goods and services made in the U.S.; consumers aren't willing to pay for "employees healthcare." Therefore for the U.S. to be economically competitive with the world, we need to reduce the cost of healthcare that is absorbed in our product costs.

* In addition to being tremendously expensive, the historical "cost-plus" environment of healthcare reimbursement has led to a grossly inefficient system with 30-50% waste due to fraud, re-work, and ill-applied medical procedures that don't result in quality outcomes, increased QoL and length of life. It is also worth noting that even if Medicare were not financially broken by inefficiency and other waste, the demographics of the baby boomer generation will break the system when more baby boomers on on Medicare than employed people putting into the system. As previously noted, much healthcare spending in the U.S. occurs at end of life, with spending in the $20-$30k level per person. If Medicare were able to reduce the waste by 50% in the system, even for just Medicare, at current projections the U.S. would save 5% of our GDP! Thus the government reform effort is focusing on implementing Electronic Health Records to drive efficiency and starting to pay for Quality (Performance) / Cost in healthcare, true value meaures, vs. "Volume" of procedures (fee for service.) The metrics of success will evolve to greater efficiency - PCP's in the U.S. see ~ 40 patients / day; in England and Singapore, they see ~ 60. Processes and procedures will need to enable physicians to perform at this level.

* To reduce Medicare spending, the gov't has introduced the concept of reducing physician payment rates, but so far lobbying has prevented the measures from being implemented. Even so, the rates haven't kept pace with expenses, so that while historically "any monkey could make $ with Medicare," now physicians and hospitals need higher-paying private insurance reimbursement as part of their insured mix to break even. And as previously noted, the % of private insured is declining as demographics shift, and employers have reached a threshold on the amount of healthcare $ they can contribute to insurance plans, so private insurance rates need to come down as well.

* One big piece of the Affordable Care Act is the Individual Mandate, which requires all citizens to obtain healthcare coverage. The concept actually originated with Bob Dole and Newt Gingrich in the 1990's as a "individual responsibility" item. This will be made possible by employer requirements and the development of state-sponsored insurance exchanges. (Many companies have already indicated that with healthcare reform, they will elect to pay the $2k govt. fine and allow employees to find insurance through the state-sponsored health exchanges.) The concept of increasing the insured base may be good, because it assumes that if people are insured they will prevent more costly healthcare, as well as contribute more productively to our economy, but the legislation has been challenged for being unconstitutional. (I WILL ADDRESS THIS TOPIC IN MORE DETAIL IN A FUTURE BLOG ENTITLED "SINCE WHEN DID HEALTHCARE BECOME AN UNALIENABLE HUMAN RIGHT?)

* So how will this all work out? I wish I had taken better notes re: a McKinsey study that laid out three options: 1) , 2) , 3) belt tightening.

Personally I believe that Option 3, "belt tightening" is exactly where are are going, first with 1) limited rationing and then to 2) more progressive measures such as "process improvements" which I introduced in a previous blog post, 3) continued innovative insurance optionsto make it affordable and accessible, and 4) dramatic implementation of Health Care Directives on the social side. True process improvement requires first of all a thorough understanding of what the process is (and I think we're believing that medicine is, after all, conducive to process and not just dr's art) and then defining how that process can be streamlined and costs taken out. This will take tremendous time & effort to maintain the quality standards that U.S. citizens expect from our healthcare system while reducing costs, but relatively simple areas may be spun out. Regina Herzliner's "focused factory" concept fits the bill here. The evolvement of Minute-Clinic and Virtuwell/Zipnosis type healthcare delivery for more simple care situations provide examples, as well as specialized surgery centers for hernia repair, cardiac, etc. FUTURE BLOG POSTS TO ADDRESS: Richard Bohmer's Care Pathways and Regina Herzlinger's Market & Consumer Driven Healthcare. "If McDonalds can make perfect french fries all the time, why can't our healthcare system deliver quality outcomes at a reasonable price?"

* Mr. Orlikoff concluded the Symposia with two thoughts from historical thinkers:

1) Darwin's dying words were "they got it wrong - it isn't survival of the strongest (fittest,) it's survival of the most adaptable", and

2) Looking to Adam Smith's Division of Labor economics, do we believe that the U.S. is going to allow physicians / healthcare to bring down the U.S. economy, or with the U.S. economy bring down physicians / healthcare?

We can guess where people will side on that battlefront. I look forward to continuing to "crack the nut" of how industry can be the lead player in reforming our healthcare system to reduce cost, increase access, and increase quality.

Tuesday, October 18, 2011

Oct 2011 - FDA Commissioner Releases Blueprint to Drive Innovation

Interestingly, the FDA, once thought of as only the watchdog of industry, is now working on defining a role for helping create solutions. The Medical Device Summit (http://www.medicaldevicesummit/) presented the following article:

"The number of new products in the development pipeline is not where we would want it to be and it's not commensurate with the medical and public health need," Hamburg said while launching the blueprint “Driving Biomedical Innovation: Initiatives for Improving Products for Patients."

This includes calls for the federal watchdog agency to improve "consistency and clarity in the medical device review process," rebuild its outreach offering for small businesses and focus on developing personalized medicine, according to a press release.

"We know that investment in biomedical research and product development are at all-time highs – last year an estimated $100 billion from the public and private sector – but the return on investment, in terms of new products for people and to the companies, has not been what was expected," Hamburg said. "Timelines are long, costs are high, rates of failure are distressingly high, so this is a critical time to come together to address this important issue for people and for our nation."

The blueprint will address seven areas, namely:

Other members of the Entrepreneurs in Residence team include: Jeff Allen, Friends of Cancer Research; Riley Crane, MIT Media Lab; Dr. Elazer Edelman, MIT/Harvard Medical; Dr. Thomas Fogarty, Fogarty Institute for Innovation; Mark Jeffrey, Kellogg School; Dean Kamen, DEKA Research; Anjali Kataria, Conformia; Jack Lasersohn, The Vertical Group; Dr. Roger Lewis, UCLA Medical Center; Dr. Jeffrey E. Shuren, FDA, among others."

| "Monday, October 10, 2011 8:02 AM |

| FDA Commissioner Hamburg Releases Blueprint to Drive Innovation |

Dr. Margaret Hamburg, Commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration has released a blueprint for spurring innovation in life sciences, saying that there aren’t enough products in the medtech pipeline.

"The number of new products in the development pipeline is not where we would want it to be and it's not commensurate with the medical and public health need," Hamburg said while launching the blueprint “Driving Biomedical Innovation: Initiatives for Improving Products for Patients."

This includes calls for the federal watchdog agency to improve "consistency and clarity in the medical device review process," rebuild its outreach offering for small businesses and focus on developing personalized medicine, according to a press release.

"We know that investment in biomedical research and product development are at all-time highs – last year an estimated $100 billion from the public and private sector – but the return on investment, in terms of new products for people and to the companies, has not been what was expected," Hamburg said. "Timelines are long, costs are high, rates of failure are distressingly high, so this is a critical time to come together to address this important issue for people and for our nation."

The blueprint will address seven areas, namely:

- Rebuilding FDA’s small business outreach services,

- Building the infrastructure to drive and support personalized medicine,

- Creating a rapid drug development pathway for important targeted therapies,

- Harnessing the potential of data mining and information sharing while protecting patient privacy,

- Improving consistency and clarity in the medical device review process,

- Training the next generation of innovators, and

- Streamlining and reforming FDA regulations.

FDA is also launching an Entrepreneurs in Residence program to bring outside experts into the fold. This includes the recently-retired Medtronic CEO Bill Hawkins (who recently assumed charge as CEO of blood screening and equipment company Immucor). This initiative is aimed at improving the agency's understanding of "the business context that is important for us to better understand as we undertake our regulatory review."

“We think that it’s very, very important that we have this kind of cross-fertilization, with industry and academia and government all working together to help ensure that we have the understanding and the systems in place and the tools that we need to be able to translate from scientific discoveries into real-world product," she said.

Other members of the Entrepreneurs in Residence team include: Jeff Allen, Friends of Cancer Research; Riley Crane, MIT Media Lab; Dr. Elazer Edelman, MIT/Harvard Medical; Dr. Thomas Fogarty, Fogarty Institute for Innovation; Mark Jeffrey, Kellogg School; Dean Kamen, DEKA Research; Anjali Kataria, Conformia; Jack Lasersohn, The Vertical Group; Dr. Roger Lewis, UCLA Medical Center; Dr. Jeffrey E. Shuren, FDA, among others."

Clearly, the FDA is recognizing that it plays a critical role in facilitating or NOT facilitating innovation in industry, and it is wise to include business leaders like Bill Hawkins in the process. We will look for more progress over time.

Wednesday, October 12, 2011

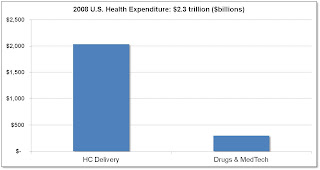

Where is the Money? Big Cost Drivers in Healthcare Spending

If industry is going to be the force that revolutionizes healthcare, money will be the driver. The question to ask is, Where is the money now and where will/should it be in the future?

I propose looking at the "where is the $" question in three different areas:

1. Hospital / Provider spending vs. Medtech / Pharma: Data shows that medtech / pharma constitute only 3% of overall healthcare spending vs. hospital / provider, which would lead to a conclusion that there may be more room for cost reduction in hospital / provider. This doesn't take into account, however, how medtech / pharma may be the driver for increased care. Here's the data:

Source: American Well: The Doctor Will E-See You Now HBS CASES | ELIE OFEK, RON LAUFER | MAR 30, 2010.

2. Chronic Disease: It makes sense that the highest cost drivers in medicine are associated with chronic diseases which require medical care over long periods of time, and also may involve expensive hospital visits. Care that is aimed to reduce hospital visits and keep people stable and as well as possible is the objective here. Below is a graph which shows an estimate of the direct and indirect costs for some of the most expensive chronic diseases to manage:

Source: An Unhealthy America: The Economic Burden of Chronic Disease. Milken Institute, Oct. 2007.

3. End of Life Spending. I wasn't able to find data on % of $ spent on end of life, but I did find the following article on racial differences that indicates between $20k-$30k of spending in the last 6 months of life:

Racial and Ethnic Differences in End-of-Life Costs

Why Do Minorities Cost More Than Whites?

Amresh Hanchate, PhD ; Andrea C. Kronman, MD, MSc ; Yinong Young-Xu, ScD, MS ; Arlene S. Ash, PhD ; Ezekiel Emanuel, MD, PhD

Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(5):493-501.

Background Racial and ethnic minorities generally receive fewer medical interventions than whites, but racial and ethnic patterns in Medicare expenditures and interventions may be quite different at life's end.

Methods Based on a random, stratified sample of Medicare decedents (N = 158 780) in 2001, we used regression to relate differences in age, sex, cause of death, total morbidity burden, geography, life-sustaining interventions (eg, ventilators), and hospice to racial and ethnic differences in Medicare expenditures in the last 6 months of life.

Results In the final 6 months of life, costs for whites average $20 166; blacks, $26 704 (32% more); and Hispanics, $31 702 (57% more). Similar differences exist within sexes, age groups, all causes of death, all sites of death, and within similar geographic areas. Differences in age, sex, cause of death, total morbidity burden, geography, socioeconomic status, and hospice use account for 53% and 63% of the higher costs for blacks and Hispanics, respectively. While whites use hospice most frequently (whites, 26%; blacks, 20%; and Hispanics, 23%), racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life expenditures are affected only minimally. However, fully 85% of the observed higher costs for nonwhites are accounted for after additionally modeling their greater end-of-life use of the intensive care unit and various intensive procedures (such as, gastrostomies, used by 10.5% of blacks, 9.1% of Hispanics, and 4.1% of whites).

Conclusions At life's end, black and Hispanic decedents have substantially higher costs than whites. More than half of these cost differences are related to geographic, sociodemographic, and morbidity differences. Strikingly greater use of life-sustaining interventions accounts for most of the rest.

Author Affiliations: Section of General Internal Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts (Drs Hanchate, Kronman, and Ash); Lown Cardiovascular Research Foundation, Brookline, Massachusetts (Dr Young-Xu); and Department of Bioethics, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland (Dr Emanuel).

So moving forward, when looking for areas to impact to reduce cost, increase access, and improve quality, the sweet spots are in hospital / provider, chronic disease management, and end of life spending. The type of solutions required will likely be quite different for each. For example, in EoL spending, there are studies showing that Healthcare Directives have had an important effect on reducing EoL spending where they are implemented.

I look forward to exploring each of these areas in detail in future posts.

I propose looking at the "where is the $" question in three different areas:

1. Hospital / Provider spending vs. Medtech / Pharma: Data shows that medtech / pharma constitute only 3% of overall healthcare spending vs. hospital / provider, which would lead to a conclusion that there may be more room for cost reduction in hospital / provider. This doesn't take into account, however, how medtech / pharma may be the driver for increased care. Here's the data:

Source: American Well: The Doctor Will E-See You Now HBS CASES | ELIE OFEK, RON LAUFER | MAR 30, 2010.

2. Chronic Disease: It makes sense that the highest cost drivers in medicine are associated with chronic diseases which require medical care over long periods of time, and also may involve expensive hospital visits. Care that is aimed to reduce hospital visits and keep people stable and as well as possible is the objective here. Below is a graph which shows an estimate of the direct and indirect costs for some of the most expensive chronic diseases to manage:

Source: An Unhealthy America: The Economic Burden of Chronic Disease. Milken Institute, Oct. 2007.

Chronic Disease Burden*:

• > 100 million Americans have Diabetes, Kidney Disease, Hypertension, and/or Cardiovascular Disease

• 2 of 3 Americans are overweight; 1 in 5 is Obese

• Chronic diseases account for 96% of Medicare Spending

• Complications from chronic disease account for ~75% of US healthcare spending!

3. End of Life Spending. I wasn't able to find data on % of $ spent on end of life, but I did find the following article on racial differences that indicates between $20k-$30k of spending in the last 6 months of life:

Racial and Ethnic Differences in End-of-Life Costs

Why Do Minorities Cost More Than Whites?

Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(5):493-501.

Background Racial and ethnic minorities generally receive fewer medical interventions than whites, but racial and ethnic patterns in Medicare expenditures and interventions may be quite different at life's end.

Methods Based on a random, stratified sample of Medicare decedents (N = 158 780) in 2001, we used regression to relate differences in age, sex, cause of death, total morbidity burden, geography, life-sustaining interventions (eg, ventilators), and hospice to racial and ethnic differences in Medicare expenditures in the last 6 months of life.

Results In the final 6 months of life, costs for whites average $20 166; blacks, $26 704 (32% more); and Hispanics, $31 702 (57% more). Similar differences exist within sexes, age groups, all causes of death, all sites of death, and within similar geographic areas. Differences in age, sex, cause of death, total morbidity burden, geography, socioeconomic status, and hospice use account for 53% and 63% of the higher costs for blacks and Hispanics, respectively. While whites use hospice most frequently (whites, 26%; blacks, 20%; and Hispanics, 23%), racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life expenditures are affected only minimally. However, fully 85% of the observed higher costs for nonwhites are accounted for after additionally modeling their greater end-of-life use of the intensive care unit and various intensive procedures (such as, gastrostomies, used by 10.5% of blacks, 9.1% of Hispanics, and 4.1% of whites).

Conclusions At life's end, black and Hispanic decedents have substantially higher costs than whites. More than half of these cost differences are related to geographic, sociodemographic, and morbidity differences. Strikingly greater use of life-sustaining interventions accounts for most of the rest.

Author Affiliations: Section of General Internal Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts (Drs Hanchate, Kronman, and Ash); Lown Cardiovascular Research Foundation, Brookline, Massachusetts (Dr Young-Xu); and Department of Bioethics, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland (Dr Emanuel).

So moving forward, when looking for areas to impact to reduce cost, increase access, and improve quality, the sweet spots are in hospital / provider, chronic disease management, and end of life spending. The type of solutions required will likely be quite different for each. For example, in EoL spending, there are studies showing that Healthcare Directives have had an important effect on reducing EoL spending where they are implemented.

I look forward to exploring each of these areas in detail in future posts.

Friday, September 23, 2011

Product vs. Process Innovation

In studying Innovation, one of the themes is that as products and industries mature, the nature of innovation shifts from PRODUCT innovation to PROCESS innovation. A professor at MIT Sloan, James Utterback, outlines this concept in Mastering the Dynamics of Innovation - How Companies Can Seize Opportunities in the Face of Technological Change (1994, Harvard College), p. 91:

In healthcare, I view the overall process to be described by this flow diagram, starting from access to diagnostics to thearpy to outcomes to Value, both clinical and economic:

With the economic system in the U.S., the medical device & pharmaceutical industry has been incented to develop tremendous technological solutions for treatment, and to some extent diagnostics as well. Therefore I would hypothesize that the PRODUCT innovation has been maximized in these two areas - i.e. the pacemakers, stents, spinal implants, drugs, MRI's, ultrasound scanners, etc. have reached close to a plateau in terms of the functional capabilities they possess. Even with greater investment in these areas, alone they cannot increase overall clinical and economic value to the healthcare system.

In contrast, technologies that enhance the FLOW, EFFICIENCY and THROUGHPUT of patients in the healthcare system have much greater potential for additional clinical and economic value. I will be looking at the problem of cost reduction in healthcare using these frameworks as my foundation.

In healthcare, I view the overall process to be described by this flow diagram, starting from access to diagnostics to thearpy to outcomes to Value, both clinical and economic:

With the economic system in the U.S., the medical device & pharmaceutical industry has been incented to develop tremendous technological solutions for treatment, and to some extent diagnostics as well. Therefore I would hypothesize that the PRODUCT innovation has been maximized in these two areas - i.e. the pacemakers, stents, spinal implants, drugs, MRI's, ultrasound scanners, etc. have reached close to a plateau in terms of the functional capabilities they possess. Even with greater investment in these areas, alone they cannot increase overall clinical and economic value to the healthcare system.

In contrast, technologies that enhance the FLOW, EFFICIENCY and THROUGHPUT of patients in the healthcare system have much greater potential for additional clinical and economic value. I will be looking at the problem of cost reduction in healthcare using these frameworks as my foundation.

Tuesday, September 13, 2011

Introductory thoughts on this Blog about Revolutionizing Healthcare through Industry

Inspired by both Daniel McGlaughlin (Director, Center for Health and Medical Affairs at University of St. Thomas in Minneapolis and former CEO of Hennepin County Medical Center, who writes a High Performance Healthcare Blog at http://blogs.stthomas.edu/hphc/) and Julie & Julia, the movie about Mastering the Art of French Cooking, I have decided to start blogging about my career passion, Revolutionizing Healthcare through Industry.

Why this topic, you might ask? Our healthcare system is plagued with high costs, low access, and quality predicaments even though we have the best technology in the world. To reduce cost, increase access, and increase quality, as a med-tech industry professional and MBA, I believe industry is best positioned to develop solutions that work. No amount of government-mandated change can effectively fix our problems as a market-driven solutions that consumers, employers, patients, providers, and payors want. This blog is about exploring the principles behind and examples of innovations that can accomplish our three goals of reducing cost, increasing access, and increasing quality.

And why me? I was recently out for coffee with healthcare guru David Dickey, currently the CEO of Second Story Sales after being one of the early employees of Definity Health which pioneered Consumer Driven Healthcare Plans and the Health Reimbursement Account, clearly great financial innovation that has already affected us all. After comparing each other's backgrounds in healthcare and medtech, Dave called me a "Forrest Gump of Healthcare," as many of us are in some way or other once we reach the ripe old age of 40. Evidence: experiencing my sister's brain tumor and care in the 1970's, attending St. Olaf at the same time as his friend Tony Miller who started Definity; starting my career in the pacing industry with Medtronic during the rise of the implantable defibrillator; writing a master' thesis on the adoption of new medical technologies; consulting post-MBA with an innovation management firm working with academic affiliates including Clayton Christenson; driving the decision for remote follow-up and heart failure sensors at Guidant; being investor #10 with QuickMed/MinuteClinic; knowing my former St. Olaf physics lab partner, David Rose, who invented GlowCaps (http://www.vitality.net/); shaking Regina Herzlinger's hand at HBS, the mother of Consumer Driven Healthcare; being a subject matter expert with WMDO.org's worldwide training programs for medtech as WMDO guides learning around the globe; and teaching my course on Marketing Medical Technologies at UST. I would say Dave is another Forrest Gump, as well as many around us in the Medical Alley / LifeScience Alley we live in here in the Twin Cities. Together with innovators and entreprenuers, I believe we possess the collective brainpower and innovation capabilities to develop truly revolutionary solutions that will cure our healthcare system, and I want to do what I can to stimulate the type of innovation that will cure our U.S. healthcare system.

Why this topic, you might ask? Our healthcare system is plagued with high costs, low access, and quality predicaments even though we have the best technology in the world. To reduce cost, increase access, and increase quality, as a med-tech industry professional and MBA, I believe industry is best positioned to develop solutions that work. No amount of government-mandated change can effectively fix our problems as a market-driven solutions that consumers, employers, patients, providers, and payors want. This blog is about exploring the principles behind and examples of innovations that can accomplish our three goals of reducing cost, increasing access, and increasing quality.

And why me? I was recently out for coffee with healthcare guru David Dickey, currently the CEO of Second Story Sales after being one of the early employees of Definity Health which pioneered Consumer Driven Healthcare Plans and the Health Reimbursement Account, clearly great financial innovation that has already affected us all. After comparing each other's backgrounds in healthcare and medtech, Dave called me a "Forrest Gump of Healthcare," as many of us are in some way or other once we reach the ripe old age of 40. Evidence: experiencing my sister's brain tumor and care in the 1970's, attending St. Olaf at the same time as his friend Tony Miller who started Definity; starting my career in the pacing industry with Medtronic during the rise of the implantable defibrillator; writing a master' thesis on the adoption of new medical technologies; consulting post-MBA with an innovation management firm working with academic affiliates including Clayton Christenson; driving the decision for remote follow-up and heart failure sensors at Guidant; being investor #10 with QuickMed/MinuteClinic; knowing my former St. Olaf physics lab partner, David Rose, who invented GlowCaps (http://www.vitality.net/); shaking Regina Herzlinger's hand at HBS, the mother of Consumer Driven Healthcare; being a subject matter expert with WMDO.org's worldwide training programs for medtech as WMDO guides learning around the globe; and teaching my course on Marketing Medical Technologies at UST. I would say Dave is another Forrest Gump, as well as many around us in the Medical Alley / LifeScience Alley we live in here in the Twin Cities. Together with innovators and entreprenuers, I believe we possess the collective brainpower and innovation capabilities to develop truly revolutionary solutions that will cure our healthcare system, and I want to do what I can to stimulate the type of innovation that will cure our U.S. healthcare system.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)