I was fortunate to attend the 12th Annual Physician Leadership Symposium University of St. Thomas on

October 17, sponsored by leading Minnesota physician William E. Petersen's endowment and presented by Allina Hospitals and Clinics, Abbott Northwestern Hospital Foundation, and the health care programs of the University of St. Thomas. The event featured consultant James Orlikoff, named one of the 100 most powerful people in healthcare by Modern Healthcare magazine and National Advisor on Governance and Leadership to the American Hospital and Health Forum, Senior Consultant to the Cnter for Health Care Governance, speaking about Leadership in a Time of Reform.

Given this daunting topic, Mr. Orlikoff did an outstanding job of distilling down the issues to the critical few, and ended with the conclusion that Medicine as Physicians now know it is over. Why? Let's take a look at a few of the points Mr. Orlikoff made about the ‘big picture’ drivers of healthcare reform:

• Why has healthcare reform passed now, after so many previous attempts? At this time, the U.S. National Debt has reached the point where we are in crisis. To get out of that crisis, we have to address Medicare as one of the largest cost drivers in the government's budget (along with Social Security and Defense.) As we remember, the U.S. economy was in limbo while the government voted on raising the debt ceiling in August 2011 to $14.3 trillion, from the $12.4 trillion level set in December 2009, the 6th time Congress raised the debt limit since 1917's Second Liberty Bond Act. The National Debt is now close to the entire annual Gross Domestic Product of the U.S., which was $15 trillion in 2011. Work is now happening in a subcommittee to find $1.3 trillion of savings by November 2011, with a Congressional vote in December; if if can't be found and agreed upon, the U.S. economy could again be thrown into a tailspin where we either 1) default on our debts, or 2) raise the debt ceiling again, both of which would have dramatic implications for the U.S. debt rating and could throw our economy into the worst depression since the Great Depression in 1929-1941. With the huge economic importance of resolving this situation, the political environment was ready to attach healthcare reform, where before the urgency didn't allow politicians to step on the dangerous turf of removing social benefit programs.

* Since introduction of Medicare by Lyndon Johnson with the Social Security Act in 1965, when the "average" life expectancy (influenced by WWII and the pandemic flu) was 65 so benefits were set at 65, the program now covers over 48 million people. Medicare was modeled after Otto von Bismarck who implemented an "illusory safety net" in Germany after WWI that provided medical covereage for people >65; at that time, 65 was life expectancy. Now it is more like 92, Also, using the AVERAGE life expectancy vs. the end value of life expectancy greatly increases the number of potential enrollees at any age, and the choice of 65 has created a great Medicare pool. (great timeline at

http://www.kff.org/medicare/medicaretimeline.cfm).

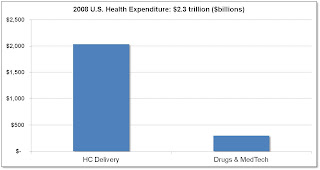

* Economically, healthcare expenditures in the U.S.were ~ 17% of GDP in 2009 , compared to 6-12% of much of the rest of the world, and are projected to be ~20% of GDP by 2020. In 2020, Medicare/Medicaid will comprise ~ 1/2 of healthcare spending, making the government effectively a single payor system for the U.S., and spending it's share, or 10% of U.S. GDP, on it. Healthcare is not "value-added" to society; though there may be measurable economic gains from healthcare spending in the workforce through increased productivity, by definition, Medicare is for people > 65 when people are no longer working, and much of our healthcare spending is at end of life as well.

* For company-sponsored health plans, each employee costs ~ $20k/year to insure. This key fact makes the U.S. extremely uncompetitive in the global marketplace for goods and services, as has been alluded to in the auto industry: for the same steel and labor costs, it still costs the U.S. xx% more to produce a car because it has to factor in healthcare costs, so that it can't set a price competitive to say, Japan, which spent ~8.5% of GDP on healthcare in 2009 and still be as profitable. When a consumer see a blouse made in the U.S. for sale for $85, and then another similar one of the same quality on the next rack selling for $15 made in China, consumers make an economic value decision for themselves; pricing in the "morality" of supporting the U.S. healthcare system expense is a losing battle in the global marketplace. (in 2001 China's spending was 5.5% GDP; now their GDP is much higher

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_health_in_the_People%27s_Republic_of_China). The same goes for ALL goods and services made in the U.S.; consumers aren't willing to pay for "employees healthcare." Therefore for the U.S. to be economically competitive with the world, we need to reduce the cost of healthcare that is absorbed in our product costs.

* In addition to being tremendously expensive, the historical "cost-plus" environment of healthcare reimbursement has led to a grossly inefficient system with 30-50% waste due to fraud, re-work, and ill-applied medical procedures that don't result in quality outcomes, increased QoL and length of life. It is also worth noting that even if Medicare were not financially broken by inefficiency and other waste, the demographics of the baby boomer generation will break the system when more baby boomers on on Medicare than employed people putting into the system. As previously noted, much healthcare spending in the U.S. occurs at end of life, with spending in the $20-$30k level per person. If Medicare were able to reduce the waste by 50% in the system, even for just Medicare, at current projections the U.S. would save 5% of our GDP! Thus the government reform effort is focusing on implementing Electronic Health Records to drive efficiency and starting to pay for Quality (Performance) / Cost in healthcare, true value meaures, vs. "Volume" of procedures (fee for service.) The metrics of success will evolve to greater efficiency - PCP's in the U.S. see ~ 40 patients / day; in England and Singapore, they see ~ 60. Processes and procedures will need to enable physicians to perform at this level.

* To reduce Medicare spending, the gov't has introduced the concept of reducing physician payment rates, but so far lobbying has prevented the measures from being implemented. Even so, the rates haven't kept pace with expenses, so that while historically "any monkey could make $ with Medicare," now physicians and hospitals need higher-paying private insurance reimbursement as part of their insured mix to break even. And as previously noted, the % of private insured is declining as demographics shift, and employers have reached a threshold on the amount of healthcare $ they can contribute to insurance plans, so private insurance rates need to come down as well.

* One big piece of the Affordable Care Act is the Individual Mandate, which requires all citizens to obtain healthcare coverage. The concept actually originated with Bob Dole and Newt Gingrich in the 1990's as a "individual responsibility" item. This will be made possible by employer requirements and the development of state-sponsored insurance exchanges. (Many companies have already indicated that with healthcare reform, they will elect to pay the $2k govt. fine and allow employees to find insurance through the state-sponsored health exchanges.) The concept of increasing the insured base may be good, because it assumes that if people are insured they will prevent more costly healthcare, as well as contribute more productively to our economy, but the legislation has been challenged for being unconstitutional. (I WILL ADDRESS THIS TOPIC IN MORE DETAIL IN A FUTURE BLOG ENTITLED "SINCE WHEN DID HEALTHCARE BECOME AN UNALIENABLE HUMAN RIGHT?)

* So how will this all work out? I wish I had taken better notes re: a McKinsey study that laid out three options: 1) , 2) , 3) belt tightening.

Personally I believe that Option 3, "belt tightening" is exactly where are are going, first with 1) limited rationing and then to 2) more progressive measures such as "process improvements" which I introduced in a previous blog post, 3) continued innovative insurance optionsto make it affordable and accessible, and 4) dramatic implementation of Health Care Directives on the social side. True process improvement requires first of all a thorough understanding of what the process is (and I think we're believing that medicine is, after all, conducive to process and not just dr's art) and then defining how that process can be streamlined and costs taken out. This will take tremendous time & effort to maintain the quality standards that U.S. citizens expect from our healthcare system while reducing costs, but relatively simple areas may be spun out. Regina Herzliner's "focused factory" concept fits the bill here. The evolvement of Minute-Clinic and Virtuwell/Zipnosis type healthcare delivery for more simple care situations provide examples, as well as specialized surgery centers for hernia repair, cardiac, etc. FUTURE BLOG POSTS TO ADDRESS: Richard Bohmer's Care Pathways and Regina Herzlinger's Market & Consumer Driven Healthcare. "If McDonalds can make perfect french fries all the time, why can't our healthcare system deliver quality outcomes at a reasonable price?"

* Mr. Orlikoff concluded the Symposia with two thoughts from historical thinkers:

1) Darwin's dying words were "they got it wrong - it isn't survival of the strongest (fittest,) it's survival of the most adaptable", and

2) Looking to Adam Smith's Division of Labor economics, do we believe that the U.S. is going to allow physicians / healthcare to bring down the U.S. economy, or with the U.S. economy bring down physicians / healthcare?

We can guess where people will side on that battlefront. I look forward to continuing to "crack the nut" of how industry can be the lead player in reforming our healthcare system to reduce cost, increase access, and increase quality.